Understanding iOS internationalization

| 2.mar.2017 | Cosmetic updates to fit new site design, added table of contents and note on the length. |

I assume reader is already familiar with basic internationalization facilities and approaches used in iOS apps development. The distinctions and details I cover in this article were a bit confusing for me when I first started introducing internationalization in my apps, so I decided to wrap it up for myself and any curious developer.

It’s a long read, but it’s not necessary to read it all at once.

- Let’s look at the settings

- Language app is running in

- Regional conventions

- Locale vs language

- Preferred languages vs preferred localizations

- How -[NSString initWithFormat:locale:arguments:] converts numbers to string representation?

- How -[NSString initWithFormat:locale:arguments] picks correct string from .stringsdict?

- How -[NSPlaceholderString initWithFormat:locale:arguments] decides which plural form to get?

- Forcing NSLocalizedString to use specific locale’s plural rules

- Using built in ICU for custom pluralization

- Base internationalization

- Localized strings keys

- NSLocalizedString comments

- I’ll add internationalization later

- When should I not use currentLocale?

- Formatting numbers and pluralization is tricky

- Resources with lots of more info

Let’s look at the settings

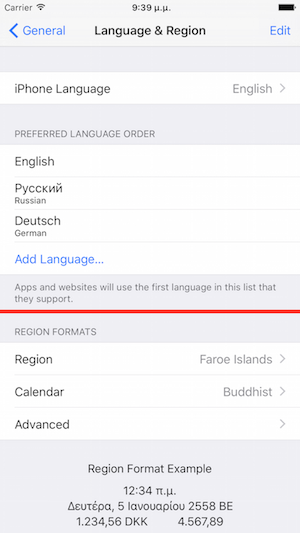

Here’s “Language & Region” settings screen in iOS 9, I have separated it in to parts with the red line:

Let’s inspect iOS Language & Region settings, parameters we’re interested in:

- system language

- list of languages user prefers including system language

- region

- region language

- calendar

This settings render behaviors which could be separated into two major distinct categories:

- Everything related to the language app is running in. You access this information via

NSBundle(and NSLocale for preferred languages, but, usually you don’t need that). Settings that specify that:system language,preferred languages. - Everything related to what regional conventions are being used for displaying locale-sensitive data, you access this information via

NSLocale. Settings that specify that:region,region language,calendar.

Important thing is that, while usually this two are the same, so that regional conventions are for the language app is running in, it may often not be the case. And we must obey our user’s will (most of the time), say, displaying strings in English, using English plural rules while presenting numbers using Russian decimal separators and dates in the Buddhist calendar.

I’ve mentioned NSBundle and NSLocale. You may think of them like this: NSLocale tells you about user settings without taking into account what your app provides. NSBundle looks at your app and tells you which of what your app provides you should use according to user settings. So, NSBundle is usually the one to ask for language. Say, there’s a girl Jane, who likes [young, handsome, broke] guys, and there is you - [middle-aged, handsome and rich]. So, for sure, you’d better use the way you look and mute about your age and wealth to get with her. If you talk to Jane’s sister, she’ll tell you about Jane’s priorities in general, that’s NSLocale. If you talk to your buddy - he’ll advice you to weight upon something you’re good at among what Jane likes, that’s NSBundle.

Language app is running in

As I’ve mentioned above, there’s a concept of the language our app is running in (or “displayed in” as of WWDC). Actually, that is languages, placed by priority, but the most significant is the first one. This languages are decided on app launch based on the localizations you provide in your main bundle and prioritized list of languages user prefers.

| Available localizations | Preferred languages | Preferred localizations |

|---|---|---|

no order |

top to bottom |

|

| it, en, ru(dev) | fr, en, ru | en |

| it, en, ru(dev) | en, pl, it | en |

| it, en, ru(dev) | en-GB, pl, it | en |

| it, en, ru(dev) | fr | ru(dev) |

NSBundle API (NSLocalizedString is just a macro that uses it) uses this information to pick correct resource for us, and that’s it. The language your app is running in tells which .lproj directory to inspect for required resource. Also this information specifies language plural rules used for .stringsdict (I’ll cover this in more details below later, note that there are issues about that in iOS9).

Check this QA: How iOS Determines the Language For Your App for some details. You can read about how localized resources are located in The Bundle Search Pattern section of the Bundle Programming Guide. Also its worth to familiarize oneself with String Resources section of the Resource Programming Guide.

Regional conventions

Regional conventions is quite an interesting topic by itself but I won’t go into big detail about that. They describe conventions based on cultural, historical and lingual context. People expect those conventions to be followed and may be seriously confused or even seduced if not. This includes, for example, how numbers and dates are formatted, how strings are manipulated (sort, search, transformation), how currency symbols are presented, even whether first name goes before last name or metric system is preferred or not. You access information about those conventions via such APIs as NSLocale, NSNumberFormatter, NSDateFormatter, AddressBook (NSPersonNameComponentsFormatter in iOS9+) and others. The list of such peculiarities could be extended, but the main thing to get is that those are vital and hard to maintain by yourself. Apple provided us with a fascinating internationalization APIs and if you didn’t yet, you should definitely familiarize yourself with them.

For more information about regional conventions (and internationalization at all) I suggest to investigate Apple’s umbrella page with links to different internationalization info (including WWDC sessions) and “iOS Internationalization, The Complete Guide” by Shawn E. Larson.

Locale vs language

Or locale ID vs language ID, “locale” vs “localization”. Yeah, they are not the same. Language or localization describes (surprisingly) language/dialect/script and locale describes region with its conventions.

“A language ID identifies a language used in many regions, a dialect used in a specific region, or a script used in multiple regions.” - Internationalization and Localization Guide

Language described by language ID, such as en could be used to describe English language used worldwide, while en-UK (note -, not _) describes English language used in United Kingdom. And you may have two different versions of text for a two, for example:

en-UK: "I have just arrived home, so I shall use my monocle to read newspaper while having my tea."

en-US: "I just arrived home, so I'm going to grab some snacks and enjoy the game."

Your .lproj directories with localized resources for languages are called after a language ID. Also you get a list of language IDs from [NSLocale preferredLanguages]. Plural forms are based on a language ID (while ICU’s uplrules_open which I’ll describe later takes locale, it’s still reasonable to consider as I’ve mentioned).

A locale ID identifies a specific region and its cultural conventions—such as the formatting of dates, times, and numbers. - Internationalization and Localization Guide

While it may look the same, locale ID is semantically different. Locale ID is composed of language ID and optional region designator (ISO 3166-1, like US for United States and FR for France) joined by underscore _. A hint to understanding is that you read it right to left, i.e. “region with specific conventions where this language/dialect/script is used”. So:

en = “some region where English is used”.

en_US = “United States regional preferences for English speakers”.

ru_US = “United States regional preferences for Russian speakers”.

zh-Hans_HK = “China, Hong Kong’s regional preferences for Chinese in the simplified script”

Locale is used when formatting locale-sensitive data like numbers, dates and names. Locale encapsulates a lot of different settings such as language (at minimum), date and number formats, currency and how different currencies are to be displayed and a lot more. Apple uses Common Locale Data Repository (CLDR) for that data, you can access that information via NSLocale API.

Locale ID may include different components, which override different preferences, for example, to override calendar to the Buddhist you may add calendar component like this: en_US@calendar=buddhist.

Preferred languages vs preferred localizations

Both of these are ordered lists of language IDs. Preferred languages is the list of languages user prefers, you can see it in the settings:

You get this list via NSLocale API: [NSLocale preferredLanguages]. First item in that list is usually a system language, language in which operation system elements and Apple apps are displayed. But this may not be the case if, for example, user sets device language to one of those which Apple did not provide localization for. For example, Afrikaans. If you at first set system language to English, then add Afrikaans and reorder preferred languages so that Afrikaans goes first, you’ll get this sequence:

1: "af"

2: "en" // system language

Apple does not currently provide Afrikaans translation for iOS or any of the system apps (like Calendar or Notes etc.), while you can. User may want to prefer Afrikaans language to English, so, If your app provides Afrikaans localization resources, it will be launched in Afrikaans while system language will still be the supported English. Note again that the first language ID in the list is not the system language in the case. Preferred languages may be used in HTTP headers, to detect system language or to implement custom internationalization SDK. You can force preferred languages by overriding AppleLanguages key via NSUserDefaults (as well as AppleLocale for currentLocale).

Preferred localizations array is generated as an intersection of what user wants and what you have ordered by preferred languages. If user prefers languages you don’t provide localization for, preferred localizations will contain your development language, i.e. value behind CFBundleDevelopmentRegion. First value from this array is the language your app is running in. NSBundle will use .lproj directory to find resources for that language ID. You can exert how preferred localizations is generated by introducing CFBundleLocalizations in your info.plist. For details see QA: How iOS Determines the Language For Your App.

A quick gotcha for .stringsdict: don’t forget to have (at least empty) .strings file with the same name for each localization you support, otherwise .stringsdict won’t be recognized and used.

As you can see now, languages and regional conventions are two distinct groups of settings, when you change value from one of the groups the other may remain untouched. So you can change system language to Chinese and that does not result in changing region to Chinese as well. And now, let’s dig into some nerdy details under the hood. As I’m always not satisfied until certain amount of understanding has been reached.

How -[NSString initWithFormat:locale:arguments:] converts numbers to string representation?

Take this lines of code:

NSLocale *locale = [NSLocale currentLocale];

NSString *format = @"Number of items: %zd";

NSInteger numberOfItems = 42;

NSString *string =

[[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:format locale:locale, numberOfItems];

NSLog(@"string = '%@' for locale %@", string, locale.localeIdentifier);

I wondered about how does it transform from NSInteger to NSString and inserts it instead of the format specifier, so I digged in with Hopper and got that it uses CFNumberFormatter. It uses core foundation’s CFNumberFormatter in __CFStringFormatLocalizedNumber called from ___CFStringAppendFormatCore. This means you can’t change formatter or configure it somehow (only via format specifier configuration like "%.6f"). You actually can cheat and format number yourself, but it gets tricky with pluralization, see corresponding section below for details.

For objects with %@ specifier it sends -descriptionWithLocale:.

How -[NSString initWithFormat:locale:arguments] picks correct string from .stringsdict?

Before I go into detail about that one, I’d like to address some fascinating issue. Consider we have an .stringsdict with a pluralized format string for a format_key key:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>format_key</key>

<dict>

<key>NSStringLocalizedFormatKey</key>

<string>%1$#@format_key_plural@</string>

<key>format_key_plural</key>

<dict>

<key>NSStringFormatSpecTypeKey</key>

<string>NSStringPluralRuleType</string>

<key>NSStringFormatValueTypeKey</key>

<string>lu</string>

<key>zero</key>

<string>ZERO</string>

<key>one</key>

<string>ONE</string>

<key>few</key>

<string>FEW</string>

<key>many</key>

<string>MANY</string>

<key>other</key>

<string>OTHER</string>

</dict>

</dict>

</dict>

</plist>

and we use it like this:

// I strongly discourage omitting comments, see "NSLocalizedString comments" below

[NSString localizedStringWithFormat:NSLocalizedString(@"format_key", nil), 42];

So, you might think that NSLocalizedString takes 42, goes through the .stringsdict xml, picks correct format string according to the plural rules and produces the result string using that format string.

Ok, I’ll rewrite this (and this will still work):

// no 42 anywhere in parameters

NSString *format = NSLocalizedString(@"format_key", nil);

[NSString localizedStringWithFormat:format, 42];

Now you see? I’ve “separated” loading format string from .stringsdict and actually using it to produce the result string. But it makes no sense, as I didn’t tell NSLocalizedString that I want the correct (plural form) format string for 42, I only gave it @"format_key" as a parameter! NSLocalizedString returns NSString, not a dictionary and +localizedStringWithFormat:(NSString *)format, ... takes NSString as a parameter.

Also, NSString must have nothing to do with .stringsdict xml loading, that means rather NSLocalizedString returns this information, or Apple is using some top mountain purple unicorn magic.

As you know, NSString is one of those Class Clusters. That means, that the real class behind “NSString” instance could be very much anything as far as it’s derivative of or binary compatible with the abstract NSString class.

If NSLocalizedString finds .stringsdict for a key it returns an instance of the special __NSLocalizedString class. __NSLocalizedString encapsulates the original string and config dictionary. The config dictionary contains info from the .stringsdict file. Here what it’s like (iOS8 and iOS9 unchanged) for the .stringsdict listed above:

format.original = "%1$#@format_key_plural@"

format.config = {

NSStringLocalizedFormatKey = "%1$#@format_key_plural@";

"format_key_plural" = {

NSStringFormatSpecTypeKey = NSStringPluralRuleType;

NSStringFormatValueTypeKey = lu;

few = FEW;

many = MANY;

one = ONE;

other = OTHER;

zero = ZERO;

};

}

As you can see it just repeats the scheme in xml. If you try to print format as is you’ll get it’s original:

NSLog(@"%@", format); // %1$#@format_key_plural@

The routine that selects correct form goes further in NSString (actually NSPlaceholderString), not in NSLocalizedString.

How -[NSPlaceholderString initWithFormat:locale:arguments] decides which plural form to get?

After intensive digging with hopper, I found references to uplrules* functions. That’s ICU. Apple does not provide headers with those functions with iPhone SDK, but you can find them here: upluralrules.h. In general, you pass it locale id and a double, it returns you the form as a string like “other” or “many”, you can read about those forms here. Below you will find an example of how to use it in your projects.

Plural rules are chosen for a preferred localization. They are not for the language your .stringsdict file is but for the preferred localization (i.e. the one that fits best what user wants and your app provides), which is, actually, the same. So it does not directly know which .lproj dir hosted the .stringsdict file, it obtains preferred localization via CoreFoundation calls equivalent to [[[NSBundle mainBundle] preferredLocalizations] firstObject] and uses plural rules for it, so it should match.

And this is really messed up in iOS 9, take this code, for example:

// language app is running in

NSLog(@"[[NSBundle mainBundle] preferredLocalizations] = %@",

[[NSBundle mainBundle] preferredLocalizations]);

// regional conventions

NSLog(@"[NSLocale currentLocale].localeIdentifier = %@",

[NSLocale currentLocale].localeIdentifier);

// as in example above

NSString *format = NSLocalizedString(@"format_key", nil);

// it should be mapped to "many" in Russian(ru) and "other" in English(en)

NSUInteger numForMany = 5;

// ru

NSLocale *ruLocale = [NSLocale localeWithLocaleIdentifier:@"ru"];

NSString *ruResult =

[[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:format locale:ruLocale, numForMany];

NSLog(@"%@ for %lu: %@", ruLocale.localeIdentifier, numForMany, ruResult);

// en

NSLocale *enLocale = [NSLocale localeWithLocaleIdentifier:@"en"];

NSString *enResult =

[[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:format locale:enLocale, numForMany];

NSLog(@"%@ for %lu: %@", enLocale.localeIdentifier, numForMany, enResult);

// currentLocale

NSLocale *currentLocale = [NSLocale currentLocale];

NSString *currentLocaleResult =

[[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:format locale:currentLocale, numForMany];

NSLog(@"%@ (currentLocale) for %lu: %@",

currentLocale.localeIdentifier, numForMany, currentLocaleResult);

And that what it outputs with language set to Russian, while regional settings are all set to english. So that currentLocale return en_US while preferred localization (the language app is running in) would be ru:

// iOS 8

> [[NSBundle mainBundle] preferredLocalizations] = (

ru

)

> [NSLocale currentLocale].localeIdentifier = en_US

> ru for 5: MANY

> en for 5: MANY

> en_US (currentLocale) for 5: MANY

That’s good, it uses correct plural rules for the .stringsdict, which contains strings in Russian for Russian plural forms. No matter which NSLocale I provide, it uses correct plural rules and formats numbers according to settings from NSLocale.

// iOS 9

> [[NSBundle mainBundle] preferredLocalizations] = (

ru

)

> [NSLocale currentLocale].localeIdentifier = en_US

> ru for 5: MANY

> en for 5: OTHER

> en_US (currentLocale) for 5: OTHER

You see? In iOS 9 it uses given locale to get plural rules for! It would use different plural rules depending on given NSLocale instance while loading the same resource in a single language. At first, WTF? It breaks the concept of two different settings - language and regional conventions. At second it breaks existing codebases. So, if you compile against iOS SDK 9.0+ and user sets different region you’ll end up with wrong text. So now, to fix that you can instead of currentLocale supply locale based on preferred language:

NSString *preferredLanguage =

[[[NSBundle mainBundle] preferredLocalizations] firstObject];

NSLocale *preferedLanguageLocale =

[NSLocale localeWithLocaleIdentifier:preferredLanguage];

NSString *result =

[[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:format

locale:prefferedLanguageLocale, numForMany];

Note, that you’re not using currentLocale, thus, even though you’ll get correct plural rules, you won’t obey to user’s regional preferences. You could try to to workaround this by composing locale using components (like @calendar=gregorian), ask everything you could from currentLocale and inject it as components to prefferedLanguageLocale, but I’m not sure that could even work and you won’t miss something. I’ve submitted rdar://22804555 about that.

ICU is implemented using plural rules based on Common Locale Data Repository (CLDR), you can find rule definitions here. As far as Apple’s internationalization API is based on ICU, it worth to check out the locale concept used in ICU.

Forcing NSLocalizedString to use specific locale’s plural rules

While I was digging CoreFoundation with Hopper I found that there was a reference to additional NSStringFormatLocaleKey key near NSStringFormatSpecTypeKey and NSStringFormatValueTypeKey. From the decompiled code it looked like if this key was present, it was used as a locale to get plural rules for. Unfortunately the value behind this key must be an locale object, not string locale-ID, so you can’t just add it along with a .stringsdict. That means that there’s only a hacky way to force locale from code:

// __NSLocalizedString from .stringsdict

NSString *format = NSLocalizedString...

// __NSLocalizedString.config

NSDictionary *configuration = [format valueForKey:@"config"];

NSMutableDictionary *mutableConfig = [configuration mutableCopy];

// force plural rules locale

[mutableConfig setObject:[NSLocale localeWithLocaleIdentifier:@"en_US"]

forKey:@"NSStringFormatLocaleKey"];

[format setValue:mutableConfig forKey:@"config"];

And this only works in iOS8-. I strongly discourage anybody from using this in production.

Using built in ICU for custom pluralization

If you’re planning to build your own internationalization SDK with different plural rules, I could suggest you to stick with what Apple did and base it on ICU. As I’ve mentioned, apple uses ICU’s uplrules_select and friends for plural form selection. Apple supplies required object code with CoreFoundation in libicucore.A.dylib. Unfortunately Apple does not provide upluralrules.h where the most interesting for the topic functions are, so you’ll have to add it yourself.

So, to make use of it, you have to get upluralrules.h, for example here and add libicucore.A.dylib just like you add frameworks in XCode. Here’s an example how you could use that:

NSString *getPluralForm(double value, NSLocale *locale)

{

NSString *localeIdentifier = locale.localeIdentifier;

// fallback to the language app is probably running in

if(localeIdentifier == nil)

{

localeIdentifier = [[[NSBundle mainBundle] preferredLocalizations] firstObject];

}

// fallback to english if something is really weird

if(localeIdentifier == nil)

{

localeIdentifier = @"en";

}

NSString *form = nil;

UErrorCode status = U_ZERO_ERROR;

// get plural rules for locale, guess this could be cached and could be expensive

UPluralRules *pluralRules = uplrules_open([localeIdentifier cStringUsingEncoding:NSASCIIStringEncoding], &status);

if(U_SUCCESS(status) && pluralRules != NULL)

{

status = U_ZERO_ERROR;

int32_t capacity = 16; // fancy random capacity so that the biggest keyword could fit

UChar keyword[capacity];

// use plural rules to obtain plural form for value

int32_t length = uplrules_select(pluralRules, value, keyword, capacity, &status);

if(length > 0)

{

form = [[NSString alloc] initWithCharacters:keyword length:length];

}

uplrules_close(pluralRules);

}

// fallback to form "other" if something went wrong

return form ?: @"other";

}

Provided method takes a double to decide plural form for and a locale to base the plural rules on. Note though, that you may not get the results you expect. For example if you expect it to return zero form for 0 it might not if in CLDR there’s no such rule for your locale. That is the case with Russian ru, in CLDR zero form for ru is not specified and 0 maps to many. Looks like Apple did something above that, using zero form for 0, so that you can supply different string like “There are no somethings” instead of “0 somethings”. And it is perfectly fine, as, according to CLDR Specifications implementations are encouraged to do so.

“However, implementations are encouraged to provide the ability to have special plural messages for 0 in particular, so that more natural language can be used.” - CLDR Specifications, Plural rules

I’ve created demo project with the code above, you can get in on github.

Now it is more clear how those groups of settings are used by internationalizations APIs. I’ve been asked a lot about how to use internationalization APIs, so I decided to include some good practices I follow here as well.

Base internationalization

It’s a fancy name for separating your storyboards/nibs UI from text, so, instead of supporting million copies of storyboard/nib you just manage million versions of .strings files and single storyboard/nib. I still don’t find it much useful as I don’t store much user facing strings in storyboards/nibs, but it really worth it. Localization native development region or CFBundleDevelopmentRegion tells which localization is your Base locale.

Localized strings keys

Apple guys like to say that the keys of your NSLocalizedStrings are in development language, the language used to create resources. They advertise it as a possibility to keep your ‘fancy’ strings around at the same time providing internationalization support.

// without internationalization

label.text = @"Text in my language";

// with intenationalization

label.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Text in my language", nil);

Here, before internationalization you had "Text in my language" string as a value, and after as a key. That’s it, your ‘fancy’ string is preserved. That could seem convenient, as in a lot of cases you’ll get your key back from NSLocalizedString and your user would see good stuff. If you don’t provide entry for the key in .strings or .stringsdict - you get the key, when genstrings generates .strings it sets value to key like that:

"Text in my language"="Text in my language";

That’s actually aiming at a leg. I don’t agree with the hype here. Using this way for localized strings key naming makes it easy to overlook missed translations (yeah, yeah, you can test and get them capitalized and NSLogged, but that is not a silver bullet). Also, you don’t provide much context with a key, or, even may provide false. You’ll for sure end up having more then one keys like “Ok”, “Cancel”, “Error occurred”, and that’s it, that is a collision, because you are using values as keys.

Localized.strings

...

/* First error text */

"Error occurred"="Error occurred";

^

/* Second error text */

"Error occurred"="Error occurred";

^ nope, you can't have two identical keys in the same file

You’ll rather have to use tables, i.e. store parts of strings in different files (which I really suggest to do, but not for the case), or, something else, maybe in code.

FirstScreen.strings

...

/* First error text */

"Error occurred"="Error occurred";

SecondScreen.strings

...

/* Second error text */

"Error occurred"="Error occurred"; /*

And, of course, you’ll have one of them changed later, so that in one case, you’ll have to use “Error occurred” and “Holy shhhhh, error!” in another, while before they were the same. What I suggest (and use myself), is a keypath-like keys. So that those two error messages could be named:

Localized.strings

...

/* First error text */

"first.error.text"="Error occurred";

/* Second error text */

"second.error.text"="Error occurred";

This approach eliminates all the described cons above, if you have missing translation this ugly dotty-english thingy appears instead of your ‘fancy’ string, so you won’t miss that. It provides more context for localizer, it happens that they don’t even see the app, only the files to translate, so it could be crucial.

NSLocalizedString comments

Use them. Really, they are crucial. They provide the most context you actually can provide.

// never do that, localizers won't understand what's that about

// you won't remember what was that about in a month

// where are the comments?

label.text = NSLocalizedString(@"Text in my language", nil);

It’s not about whether use them or not, but about what to supply. The rule of thumb for me is to provide all the information needed for localizers to understand what that string is about by only using the .strings file itself. That means that localizers should be able to translate your strings having only the .strings files you provide, they even might not have the app. And this really happens, often localizers are just only given the strings files to translate.

I’ll add internationalization later

If your app supports only single language it could be tempting to hardcode the locale or even don’t use the internationalization APIs at all. This could seem a time-saver and all-the-things-simplifier, but the time saved does not worth it and, actually, this usually takes more time if internationalization APIs were not used from the day 0. Even if you’re not planning to support multiple languages, separating text from code is a significant thing to do. I don’t suggest to go crazy and, say, always support RTL UI in a flashlight app, you (or your product owner) should just be reasonable and decide based on your target auditory not if at all but at how much you should introduce internationalization APIs in your app. At least use NSLocalizedString so you could extract and provide your .strings to your editors in minutes and, after that, update all the text in the app by the means of just replacing the files.

When should I not use currentLocale?

Most of the time if you are to supply an NSLocale instance somewhere it should be obtained rather via +[NSLocale currentLocale] or +[NSLocale autoupdatingCurrentLocale]. But there are cases when you better not. One of such examples is when you use NSNumberFormatterSpellOutStyle with NSNumberFormatter. Your app runs in some language, thus .strings files are from according .lproj dir in some language. Here you better use locale based on the language app is running.

The main thing is that you should always think and not blindly supply currentLocale everywhere you see NSLocale argument.

Formatting numbers and pluralization is tricky

Say, you need to have pluralized string and format numbers in some way that format specifier does not allow, for example spell out. You actually can do that, you may have two arguments and base your .stringsdict plural rules on the first one while inserting second one, like this:

<key>custom_format</key>

<dict>

<key>NSStringLocalizedFormatKey</key>

<string>%1$#@custom_format_plural@</string>

<key>custom_format_plural</key>

<dict>

<key>NSStringFormatSpecTypeKey</key>

<string>NSStringPluralRuleType</string>

<key>NSStringFormatValueTypeKey</key>

<string>lu</string>

<key>one</key>

<string>%2$@ something</string>

<key>other</key>

<string>%2$@ somethings</string>

</dict>

</dict>

and use it like this:

NSUInteger number = 42;

// no comments for the sake of compactness

NSString *format = NSLocalizedString(@"custom_format", nil);

// spell out number formatter uses language from locale

NSString *preferredLanguage =

[[[NSBundle mainBundle] preferredLocalizations] firstObject];

NSLocale *locale = [NSLocale localeWithLocaleIdentifier:preferredLanguage];

// configuring number formatter

NSNumberFormatter *numberFormatter = [[NSNumberFormatter alloc] init];

numberFormatter.locale = locale;

numberFormatter.numberStyle = NSNumberFormatterSpellOutStyle;

NSString *spelledCount = [numberFormatter stringFromNumber:@(number)];

NSString *string = [[NSString alloc] initWithFormat:format

locale:locale,

number, spelledCount];

Yeah that’s the option, but you should be extremely careful with this technique. What you a doing here is actually selecting plural form for one number and displaying completely another number. This looks safe for spell out style, but what if you do some rounding or precision adjustment? You may end up having number and formatted number be mapped to different plural forms. For example, if you do some rounding like maximumFractionDigits on a NSNumberFormatter, have 1.1 and round it to 1. In Russian 1.1 maps to other, while 1 maps to one! I suggest you to be reasonable and careful, don’t make any assumptions.

Resources with lots of more info

If you are looking for some deeper insight on the topic, here are some relevant sources I find appropriate:

- Apple’s umbrella page with links to different internationalization info (including WWDC sessions)

- objc.io 9 - String Localization

- “iOS Internationalization, The Complete Guide” by Shawn E. Larson

- Dark corners of Unicode by Eevee, for quick details on Unicode

- NSHipster - NSLocale

- Unicode CLDR Project

- International Components for Unicode

- plurrule.h and around there, comments are quite helpfull

- Technical Q&A QA1828: How iOS Determines the Language For Your App

- upluralrules.h

- CFBundle_Locale.c from apple open source git mirror

- My talk from 2015 (in Russian) on the topic

Tweet